Effective communication is a significant part of every job, discipline, and career! To help you develop this skill, you may take a UW Composition course from the Expository Writing Program (EWP) as well as other courses with a Writing credit. The EWP courses are typically centered around in-class discussions, short assignments, and major papers, and the bulk of the final grade comes from a final portfolio, which includes revised assignments.

With every assignment, start by focusing on the prompt and its scope, which will give you more direction about the writing task: are you supposed to craft an argument, tell a story, or connect two different texts?

Try this: If you're struggling to come up with a response to the prompt, set a 20 minute timer and start brainstorming ideas or topics that you could explore, and feel free to look back at your class notes for this! If you're still stuck, make an appointment with your professor or discuss your ideas with peers in class.

Writing in college can be different from writing in high school, so here are some tips to keep in mind when structuring academic essays and ensuring that you are keeping audience, conventions of the genre, and use of relevant evidence in mind:

Every paper needs a title, which shouldn't be the name of the assignment. Typically, it should indicate something specific about your argument.

If you're struggling writing a title, it can sometimes be beneficial to leave that step until you're done writing. Look at the themes you've developed in your paper and brainstorm ideas from those.

Two-fold titles are very common, i.e., “Something catchy/interesting/metaphoric: Something that ties to the argument.”

Try out an exercise to help brainstorm ideas for writing a title.

Most of the writing process will be spent devising your thesis statement, so focus on creating a thesis that is specific, supportable with evidence, and matters to the reader.

An introduction will act as the bridge between your readers' lives and your analysis, and it should be a primer for the argument or topic you will explore in subsequent paragraphs.

You can think of the introduction as a "funnel" for your ideas. In other words, the ideas in your introduction will go from being broad (i.e. bilingualism in America) to specifically describing the argument of your paper (As evidenced by the research of XYZ sources, being bilingual is a strength of perspective that empowers students to empathetically understand the needs of their peers).

When writing an introduction, it's recommended to include:

Hooks are common in high school writing and often take the form of anecdotes or quotes from famous people, or rhetorical questions. If you've ever read a paper that starts with "According to Webster's Dictionary, culture is defined as.." you know exactly what we're talking about. Try to avoid ledes like this in college writing as they will lead you away from your argument and set the tone of your essay as noticeably conversational.

Try this: Think about how you can introduce an interesting question or fact that's related to your topic. Is there a common dilemma or discussion related to your topic or the field?

There is different terminology for every discipline, class, and instructor: argument, focus, claim, thesis, thesis statement, focus sentence, claim with stakes. However, they all mean same thing— an academic claim with meaningful repercussions.

Many of the UW Composition/English classes require students to write a complex claim, which should 1) be arguable/nuanced, 2) take a specific stance, 3) be substantiated with evidence, and 4) have stakes and answer the question, "why does it matter?”

In college writing, the main goal of a topic sentence is to communicate what the paragraph will prove/argue/explore, rather than introduce its general focus. Instructors will often call topic sentences “sub-claims” because they support the thesis and introduce different aspects of the assignment's thesis.

With each topic sentence, focus on building your argument. In other words, each paragraph should support the claim of your thesis and build on the evidence from previous paragraphs.

When picking quotes, use the essential portion of a quote and give it context i.e. “According to So-and-so, XYZ is a common theory.” Quotes must be incorporated grammatically and can be adjusted using brackets to clarify phrases, for example: "[In the case of the Amazon river] water flows uphill" (Miller 14).

After including a quote, be sure to add an in-text citation, which will look differently depending on the required citation style, and provide specific analysis that connects your quote or evidence with the paper's overall argument.

Unless your instructor asks for personal experience, use it sparingly and only to reiterate a point found in other evidence. Personal experience is certainly appropriate for an outcome reflection or writer's memo, but it is typically not included in academic essays. Focus on providing examples and evidence through reputable articles, peer-reviewed sources, or journals - the UW Library Databases are a great place to start looking.

This is the final section of your paper, and it has two main tasks:

If you're struggling to come up with a conclusion, ask yourself, "Why should the reader care?" and see if you start to answer this question in your conclusion. Read more tips for writing a conclusion through this handout on the UNC's Writing Center page.

Topic sentence = what will be proven

Concluding sentence = why that matters

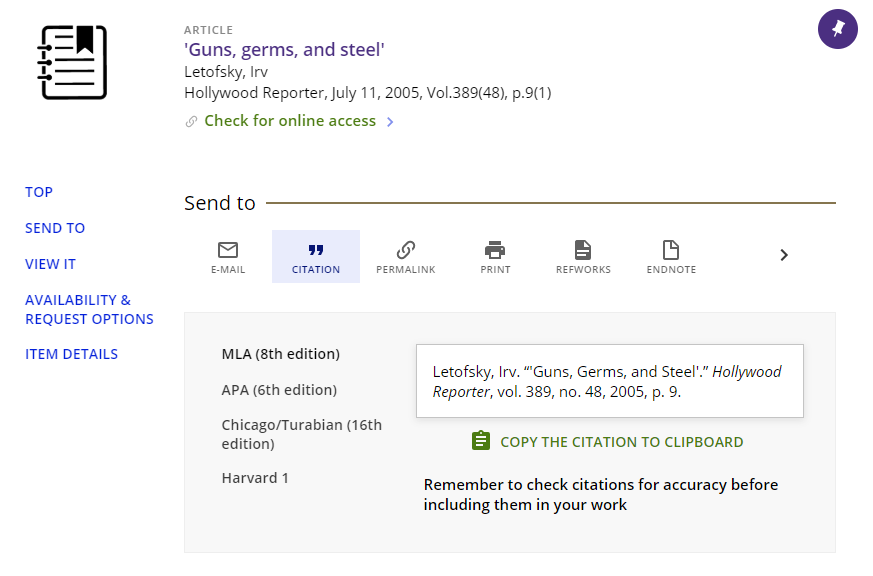

Citations are required and the use of someone else’s work without giving permission is considered plagiarism. Use both in-text citations when using quotes or referencing information that's on your own, and include a Works Cited/Bibliography page at the end of the entire document.

Proofreading your paper to ensure that your assignments are free of errors is part of turning in a polished draft. Here are some common grammar mistakes to look for as you work through your paper, as adopted from Harvard's Tips for Grammar, Punctuation, and Style:

Here are some notes to keep in mind when working on academic writing:

2-3 sources of evidence is a good goal for most paragraphs. There is no literal limit on length, but paragraphs exceeding one page usually wander. To avoid this, make sure every paragraph contributes a new piece of analysis.

Unless otherwise noted, your audience is an average educated reader. Thus, you should explain jargon/course terms, provide context for examples/evidence, and make explicit connections between your quotes/evidence and the argument of your paper.

Try to maintain a tone that is professional, clear, objective, and makes a clear argument via a logical progression of thought.

When it comes to writing for a specific audience, think about their expectations or familiarity with the topic, and write with that in mind.

Academic papers, especially when referring to literature, are typically written in present tense. This gets confusing in papers that deal with social/cultural phenomena, history, or anything that has literally already “happened.” In these instances, you can present anything from your sources in present tense, and anything from general knowledge in present perfect, past perfect, or present perfect continuous, i.e. “this has happened,” “this had happened,” or “this has been happening.”

For most academic essays where you're not presenting your own words or argument, avoid using “I,” “my,” “we,” and “our.” This topic is somewhat debatable; check with your instructor for more information.

These can be acknowledged, but typically should never contribute to sub-claims or the main claim. It can be helpful to chat with your professor or TA about your claim if it seems controversial, which can be hard to navigate in an academic paper. In general, claims should only speak on controversial topics in terms of what can objectively be proven, as the academic community will not respond to anything else.

A rhetorical question is asked in order to make a point, or produce an effect, not provide an answer. These are typically avoided in college-level writing because you as the writer are typically answering a question or forming an argument in the assignment. More importantly, rhetorical questions take for granted that the reader understands your implied answers to the question. As a responsible writer, you should assume that unless made explicit, your points will not be comprehensible to the reader.

The University of Washington’s writing centers are staffed by knowledgeable tutors who can help you workshop your assignments at any point of the process:

Icons by Freepik, xnimrodx, Nhor Phai and prettycons from www.flaticon.com.